Systems thinking is not a new concept, but it has been gaining renewed attention in recent years from public institutions and NGOs to forward-thinking private companies. And rightly so.

In this article, we explore why sector development should be approached through a systemic lens, rather than relying on a linear perspective that reduces complex challenges to simple cause-and-effect relationships. We illustrate this approach with a recent example from our work in Mozambique, demonstrating its relevance and practical impact.

While the term systems thinking is increasingly common, it is far more than a collection of buzzwords. At its core lies the aspiration to truly understand how the various elements within a system interact and influence one another, rather than isolating and analysing parts in isolation. It acknowledges the complexity of the system, not to complicate things, but to ultimately make more sense of it. In our work, this approach facilitates the design of context-specific actions and interventions that are more likely to yield meaningful and lasting change. Instead of addressing only surface-level symptoms, systems thinking helps uncover root causes and structural patterns, allowing for smarter, more sustainable solutions.

This way of thinking can be applied to virtually any setting, whether you’re a manufacturing business assessing the ripple effects of your operations or a development organisation aiming to drive real impact. At its simplest, systems thinking is about zooming out to see the bigger picture. This broader perspective not only enhances the effectiveness of your actions but also helps minimise unintended negative consequences elsewhere, a factor often overlooked yet critically important.

This greater understanding enables more informed decision making, effective resource allocation in those areas you intend to make a difference and a reduction in negative externalities in those areas that could even be in your blind spot. Uncoincidentally, these benefits are all in line with Larive’s motto: good preparation ultimately shortens timelines, lowers costs, and minimises the risks associated with operating in emerging markets. Systems thinking is a critical part of this preparation, especially in emerging markets, where dynamics are often volatile and multi-layered. This approach helps avoid costly missteps and, more importantly, creates a meaningful impact.

From concept to practice | Applying systems thinking in Mozambique’s food system

To move beyond theory, it’s essential to explore how systems thinking looks in practice. A recent initiative in Mozambique offers a compelling example of what it means to address root causes rather than symptoms. This is particularly relevant in the context of food and nutrition security, where challenges are deeply interconnected and cannot be solved with one-dimensional approaches.

The Programmatic Approach for Sustainable Economic Development (PADEO), spearheaded by the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs, embodies this philosophy. Implemented with support from the Netherlands Enterprise Agency (RVO), the approach commissioned Larive, together with our regional partner in Mozambique, to perform two comprehensive systems analyses focused on Mozambique’s food system, with a specific emphasis on the Beira Corridor and Cabo Delgado.

From complexity to clarity with Systems Thinking

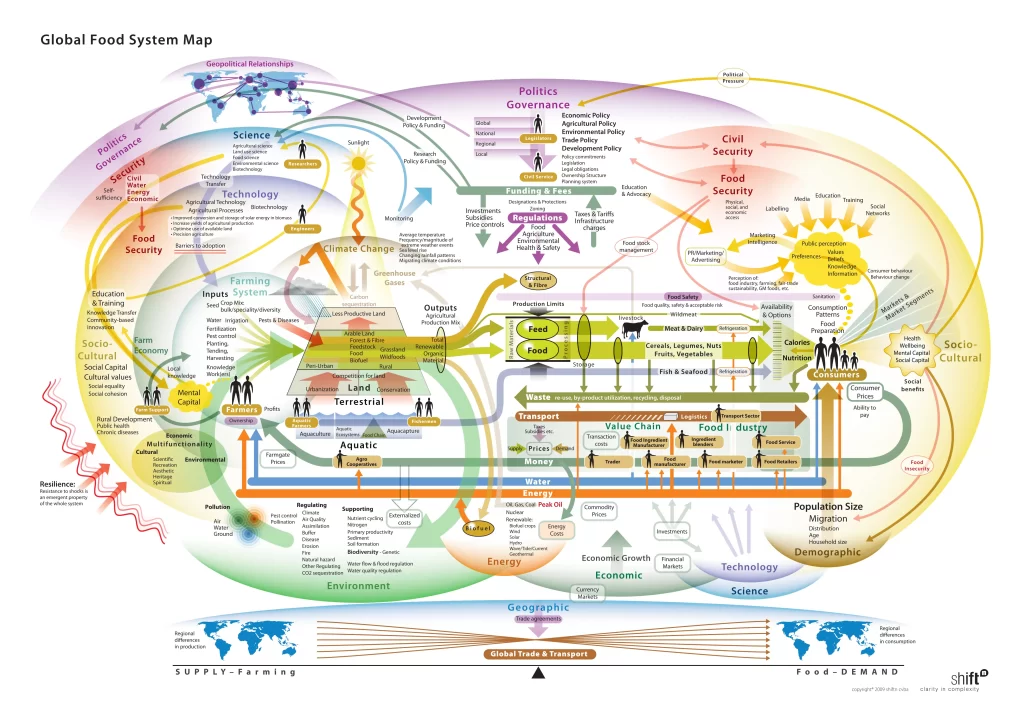

To most of us, mentally picturing the food system is already a complex challenge. But when thoroughly visualised, the interconnectedness of all the elements becomes undeniable. A single picture of the system reveals a dense web of relationships and feedback loops that shape the events we see on the surface in Mozambique: persistent food insecurity, low commercialisation of MSMEs, and widespread malnutrition.

The PADEO analysis applied the ‘systems thinking’ method rigorously. Using frameworks like the four levels of thinking, the team delved below surface-level problems to uncover patterns, structures, mental models, and root causes. Through 56 interviews conducted both in Mozambique and the Netherlands, as well as five co-creation workshops with the diverse local stakeholders, the effort brought together a wide range of contributors, from government and NGOs to community representatives and less-heard voices often excluded from development dialogue.

A context-aware approach

Importantly, the analysis recognised Mozambique’s diversity, not only across provinces but within them. It avoided a “one-size-fits-all” perspective and took into account a host of factors within and beyond the traditional view on value chains, including:

- The dynamics of conflict in Cabo Delgado.

- Internal displacement.

- Natural resource endowments.

- Socio-cultural nuances.

- Historical patterns ranging from (de)colonisation to aid and development.

Too often, these elements are glossed over. Here, they became central to understanding the system.

The team mapped feedback loops and stakeholder relationships to ultimately identify high-leverage intervention points; those with the potential to shift the system fundamentally. The outcome was a series of cross-cutting interventions, each designed not just to solve an isolated problem, but to influence several interconnected challenges simultaneously.

Important to this process is the focus on speaking to non-usual suspects, those people often left out of decision-making processes, where the usual suspects also often remarked being fatigued by being interviewed without seeing change. It also meant designing data collection processes that ensured safe spaces for honest input, free from fear of political or social repercussions.

From this, a set of principles emerged to guide future interventions. To list only a few lessons learned from the extensive list:

- Commit to understanding the local power dynamics and sensitivities.

- Design strategic interventions that complement rather than duplicate existing initiatives.

- Learn from what has worked, or just as important, what hasn’t.

- Maintain a critical lens on the gap between the available information and lived reality.

The ultimate goal was to contribute meaningful input to Mozambique’s broader food and nutrition security efforts. By highlighting the deeper, often invisible dynamics at play, the systems analysis equips policymakers and implementers to act more strategically, more inclusively, and with greater resilience, which is directly applied in the larger Food & Nutrition Security programs that are currently active. Informed decision making does not magically solve all problems, but it does ensure initiatives are more effective and respectful to the context and beneficiaries.

Are you ready to move beyond treating symptoms and start addressing systems instead? Download our ‘Systems thinking’ cheat sheet on our Insights & downloads page or connect with Claudy Luft or Niels Kreijger to explore how we can support you in creating a lasting impact.